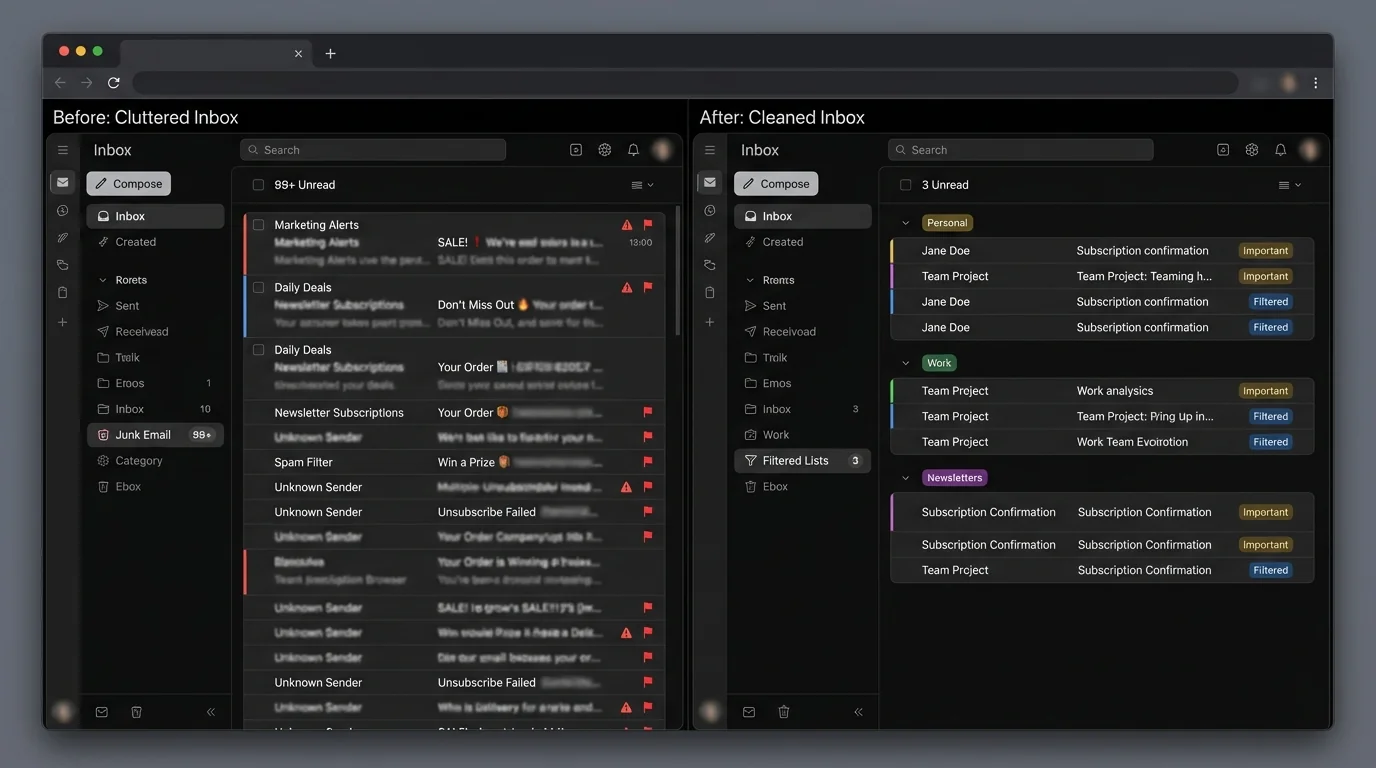

1. The problem

People search “unsubscribe button not working” when they’ve already done the “right thing” and the email keeps coming. Sometimes the link is broken. Sometimes the sender ignores the request. Sometimes the sender rotates domains or list infrastructure and you get re-added. In practice, unsubscribe is not a control plane you own—it’s a request to a system you don’t operate.

The pain shows up in three measurable ways:

- Time waste: minutes per day spent triaging, deleting, re-unsubscribing, and checking spam folders “just in case.”

- False positives: aggressive cleanup (rules, AI sorting, bulk actions) can misplace legitimate email—deliverability and trust degrade.

- Security anxiety: clicking “unsubscribe” can itself be risky, because attackers use it to confirm a live address or send you to phishing pages.

What makes this problem stubborn is that unsubscribe failures aren’t a single bug. They’re the natural result of multiple weak links: sender compliance, header configuration, ESP migrations, list hygiene, client behavior, and adversarial abuse.

2. Methodology breakdown

Below are the main methodologies people use when unsubscribe fails. Notice we’re comparing approaches, not brand names—because methodology determines reliability.

Method 1: Manual rules and user-defined filters

How it works: You create rules (filters) by sender, domain, subject keywords, or headers and route messages to folders, archive, or delete.

Where it shines:

- Predictable for stable senders (same domain, same From address).

- Can be very precise for a narrow use case (e.g., “all receipts go to Receipts”).

- No need to trust third parties—uses native mail features.

Where it fails:

- Sender changes domain or address structure → your rule stops matching.

- Rule sets grow until they become their own system to maintain.

- Rules typically operate on superficial fields (From/Subject), which are easy to vary.

“broke when sender changed domain” (common support-forum pattern)

“too many rules to manage” (common user complaint)

A sysadmin described repeatedly unsubscribing only to have emails restart, suspecting mailing lists that re-add unsubscribed addresses. (https://www.reddit.com//r/sysadmin/comments/12m47xh?utm_source=openai)

Another user reported “unsubscribe links” that were just plain text that did nothing. (https://www.reddit.com/r/assholedesign/comments/11zzmov?utm_source=openai)

Engineering verdict: Manual rules don’t fail because users are bad at rules—they fail because the sender namespace is not stable. As senders rotate domains, vendors, and templates, rule coverage decays. At scale, you end up with a brittle “patchwork firewall” maintained by a human.

Rules also increase the blast radius of mistakes. One overly broad filter can silently bury real messages.

Method 2: AI and heuristics-based sorting

How it works: A model classifies emails into categories (spam, promotions, “other,” etc.) using content and sender signals; then it routes them automatically.

Where it shines:

- Low effort: minimal setup.

- Good at catching obvious bulk mail patterns quickly.

- Helps when volume is high and you need “good enough” triage.

Where it fails:

- False positives: important emails can be classified as low priority or spam.

- Concept drift: sender behavior changes faster than models adapt.

- Trust problem: users end up checking Spam/Other daily—negating the benefit.

Many complaints follow the same pattern: “it missed something important,” or “now I have to check spam every day.” That’s not just UX—it’s an engineering symptom: if users must routinely audit the model, the system has shifted work from inbox triage to model oversight.

Engineering verdict: AI sorting optimizes for average-case accuracy, but your inbox is not an average system. The cost of a false positive is asymmetric: one missed invoice, legal notice, or customer email outweighs hundreds of correctly sorted newsletters. In engineering terms, the loss function users care about is not the one most consumer sorting systems optimize.

If 1% of legitimate emails are misclassified and you receive 50 legitimate emails/day, that’s ~0.5 emails/day → ~180 misplacements/year. Even if you “only” miss 10 of those, the trust hit is permanent.

Method 3: Blocklisting and basic allowlisting (static lists)

How it works: You block specific senders/domains (blocklist) or allow certain ones (allowlist). Some systems apply centrally managed lists.

Where it shines:

- Blocking is fast when a specific sender is clearly abusive.

- A small allowlist works for tightly scoped inboxes (a shared mailbox, a role address).

- Easy mental model.

Where it fails:

- Domain churn: senders rotate domains/subdomains and bypass blocks.

- Third-party sending: legitimate brands use multiple ESPs; blocking one can break needed mail, and allowing one can be too permissive.

- Reactive posture: blocklists grow forever and still lag new sources.

Users frequently advise: “mark as junk or block” when unsubscribe feels suspicious. (https://www.reddit.com/r/YouShouldKnow/comments/jol7e0?utm_source=openai)

Engineering verdict: Blocklists are a “signature-based” approach in a world of cheap identities. When it costs almost nothing to create a new sending domain, blocklists become an infinite treadmill. Basic allowlisting helps, but most implementations are porous (e.g., allow by domain, which can be abused if that domain later sends unwanted mail).

Allowlisting by domain is only as safe as that domain’s security and sending governance. Compromise or vendor misuse turns your allowlist into an attack path.

Method 4: Protocol-based unsubscribe (List-Unsubscribe headers)

How it works: Legit senders add List-Unsubscribe and sometimes List-Unsubscribe-Post headers so your mail client can offer a native “unsubscribe” UI that triggers an email (mailto:) or HTTP endpoint.

Where it shines:

- Best-case experience is excellent: true one-click opt-out.

- Safer than clicking random links in the email body because the action is initiated by the client UI.

- Aligns with compliance expectations when correctly implemented.

Where it fails:

- Misconfigured headers (broken URLs, invalid mailto, missing endpoints).

- Backends that don’t process requests reliably.

- Multi-step flows that violate “simplicity” expectations and increase abandonment.

Suped notes unsubscribe failure commonly stems from misconfigured headers, invalid URLs, or backends not processing opt-outs. (https://www.suped.com/knowledge/email-deliverability/troubleshooting/how-does-the-unsubscribe-from-sender-option-work-and-what-should-i-do-if-it-fails?utm_source=openai)

SMTPedia highlights that multi-step or broken flows can create legal/compliance issues. (https://smtpedia.com/email-unsubscribe-laws/?utm_source=openai)

Forbes reports cases where senders ignore client-initiated unsubscribe and the client may route messages to spam instead, risking loss of legitimate messages. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/barrycollins/2025/10/10/companies-ignore-gmails-unsubscribe-feature/?utm_source=openai)

Engineering verdict: Protocol-based unsubscribe is the most “correct” standards-driven solution—when everyone cooperates. But it is still sender-controlled. If the sender ignores requests, breaks the endpoint during a migration, or intentionally games the system, you are back to triage.

Protocol unsubscribe is best viewed as a polite request with variable reliability—not an enforcement mechanism.

3. Comparison table

| Methodology | False Positives (legit mail lost) | Time Cost | Maintenance | Security |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual rules | Medium–High (rule mistakes, overbroad matching) | High (ongoing triage + rule edits) | High (rules decay as senders change) | Moderate (less link-clicking, but junk still reaches you) |

| AI/heuristics sorting | Medium (depends on model + your tolerance) | Medium (but often requires auditing) | Medium–High (concept drift, tuning) | Moderate (reduced clicking, but misroutes can hide important mail) |

| Blocklisting / basic allowlisting | Low–Medium (blocking can be safe; allowlisting can be risky if too broad) | Medium (constant new blocks) | High (reactive treadmill) | Good for known bad; allowlist can be an attack path if compromised |

| Protocol List-Unsubscribe headers | Low (when it works) | Low–Medium (retries, failures, repeated requests) | Medium (depends on sender ecosystem health) | Better than body links; still not fully enforceable |

| Strict allowlisting (contact-first filtering) | Very Low (known-good passes) | Low (less triage) | Low–Medium (curate who’s allowed) | Strong (minimizes exposure to unknown senders and link traps) |

4. The winner: strict allowlisting

Unsubscribe failures reveal a core architectural truth: you can’t reliably “opt out” of systems you don’t control. So the scalable fix is to stop treating the open inbox as the default.

Strict allowlisting inverts the problem:

- Instead of trying to identify all bad mail (an unbounded set), you only accept known-good senders (a bounded set).

- Instead of relying on sender compliance (unsubscribe), you enforce policy on your side of the boundary.

- Instead of chasing domain churn with blocklists, you treat unknown senders as outsiders by default.

This is the same reason “default deny” wins in network security. The set of legitimate services you need is finite; the set of possible attack sources is not.

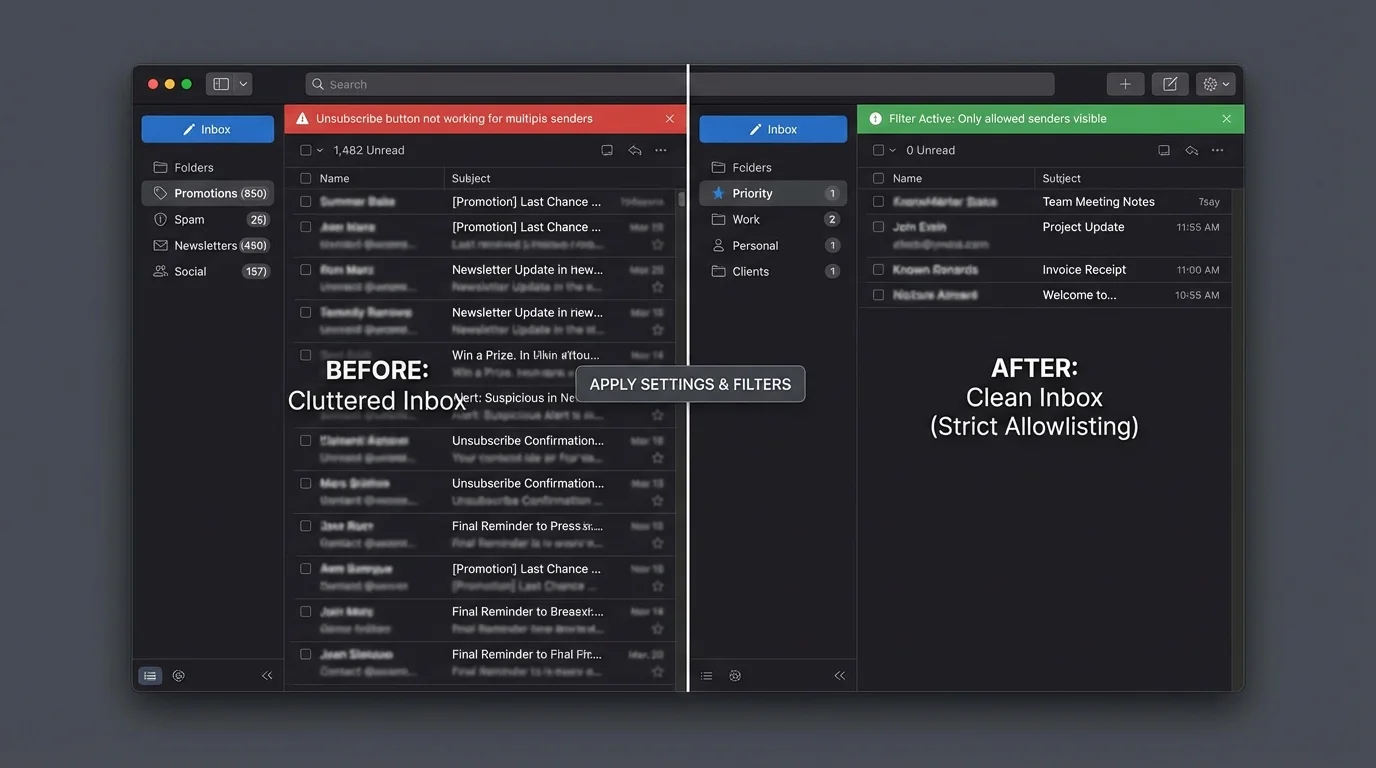

What strict allowlisting looks like in email

At an engineering level, strict allowlisting requires:

- A stable identity source for “known” senders (contacts, directory, or curated allowlist).

- A server-side enforcement point (so it’s not dependent on a local plugin).

- A safe quarantine path (so unknowns aren’t deleted, just separated).

KeepKnown implements this as an API-based email filter (server-level, not a plugin) that moves non-contacts into a dedicated label/folder: “KK:OUTSIDERS.” It supports Gmail/Google Workspace and Outlook/Microsoft 365, and uses OAuth2 with a verified security posture (CASA Tier 2) and encrypted hashes (no plaintext storage). Learn more at https://keepknown.com.

Why this wins architecturally

- Bounded maintenance: You maintain a list of who you trust, not a growing catalog of threats.

- Lower false positives than AI sorting: Known senders are deterministically allowed; you’re not guessing with a classifier.

- Security improvement: Unknown senders are separated before you ever interact with their links, reducing exposure to unsubscribe traps.

This matters because “unsubscribe” is increasingly a security decision, not just a preference.

Investopedia warns that clicking unsubscribe can expose you to phishing or confirm your address is active. (https://www.investopedia.com/why-not-to-click-unsubscribe-11765744?utm_source=openai)

Indian Express describes the “unsubscribe button trap” as an emerging cybercrime tactic. (https://indianexpress.com/article/technology/the-unsubscribe-button-trap-why-your-inbox-declutter-could-be-a-cyberattack-10106102/?utm_source=openai)

And security commentary notes that client-rendered, header-based unsubscribe is safer than body links because it reduces exposure to embedded malicious content. (https://smyservices.com/news/tech-insight-why-clicking-unsubscribe-can-be-risky/?utm_source=openai)

Strict allowlisting goes a step further: it reduces the need to unsubscribe from unknown senders at all.

A good mental model: unsubscribe is “permissionless best-effort.” Allowlisting is “policy enforcement.”

If you want the deeper conceptual comparison, see: AI Email Sorting vs Whitelisting for Inbox Control.

5. When other methods still make sense

Strict allowlisting is the strongest architecture for inbox control, but there are real edge cases where other methods are rational.

Use protocol-based unsubscribe when the sender is clearly legitimate

If it’s a reputable sender and your mail client shows a native unsubscribe UI (driven by List-Unsubscribe headers), that’s often the lowest-effort choice.

Avoid clicking unsubscribe links inside suspicious email bodies. Prefer the mail client’s native unsubscribe UI when available.

Use manual rules for narrow, stable workflows

If you have a small number of stable patterns (e.g., automated reports from a single system), manual rules are fine. Just treat them like code: document them and review them occasionally.

For a precision walkthrough, see: How to Set Up Gmail Filters (Precision Tutorial).

Use blocklisting for obvious abuse bursts

If you’re being hit by a short-term barrage, blocking can reduce noise quickly. It’s especially useful during spam waves.

If the problem is an attack-style flood rather than “newsletters,” you may be dealing with a different category entirely—see: How to Stop Gmail Spam Bombing Fast.

Use strict allowlisting for ongoing peace

If your primary problem is: “I’m done negotiating with random senders,” strict allowlisting is the only approach that doesn’t degrade with time. It reduces decision fatigue and the constant background stress of inbox pings.

If you prefer the productivity framing, see: Stop Organizing Email Start Screening It.

6. Verdict

If your unsubscribe button isn’t working, the real issue is that unsubscribe is not enforcement. Rules, AI sorting, and blocklists are all variations of “manage the bad,” which is unbounded and adversarial. Protocol-based unsubscribe is a step up, but it still depends on sender compliance and operational correctness.

The methodology that wins on engineering fundamentals is strict allowlisting (contact-first filtering): default deny for unknown senders, with a safe quarantine. It minimizes false positives from guesswork, lowers ongoing maintenance, and reduces security exposure from unsubscribe traps.

If you want a server-level implementation of this approach across Gmail/Google Workspace and Microsoft 365, KeepKnown applies strict allowlisting by moving non-contacts to “KK:OUTSIDERS.” More details at https://keepknown.com.